U.S. Meeting of RIAS Fellows 2007

Las Vegas, April 14/15, 2007

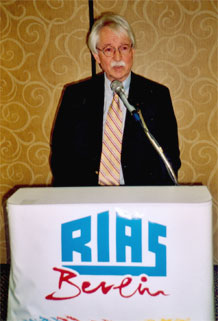

About 100 alumni, station hosts and representatives of U.S. partner universities attended the reception on April 14 and the breakfast on April 15 with guest speaker Ruediger Lentz, Bureau Chief Deutsche Welle, Washington Bureau, who offered his views and comments on “Transatlantic Relations: Perceptions and Misperceptions in the Media and by the Public about our Mutual Relations and Image.”

Ruediger Lentz

Bureau Chief

Deutsche Welle

Washington Bureau

Transatlantic Relations:

Perceptions and Misperceptions in the Media and by the Public about our Mutual Relations and Image

Let me start with some preliminary remarks:

1. Having been a correspondent for Deutsche Welle in the U.S. for more than 8 years and, before that, a European correspondent based in Brussels for more than 7 years, plus being of German origin and upbringing, I have three souls in my chest: a German one, a European one and one with a great affection for the United States. Having said this, all the following remarks should be considered those of a friend, who tries to understand and analyze recent and current events that have had and continue to have a deep impact on transatlantic relations.

2. The topic addresses the question of whether or not “perceptions and misperceptions” exist in our mutual relations. The answer is an easy one: They exist, they have existed in the past but never have those mispercep-tions grown into a transatlantic rift of such proportions.

3. This best exemplified by two different surveys in Germany that underline an existing and possibly growing anti-American sentiment among the German public that can easily be exploited for political purposes. Case No. 1: A recent poll of the German weekly “Der Stern” showed that a majority of Germans thinks that the U.S. is a greater threat to world peace than Iran. This should be of concern, not only to the Americans but also to us, the political elite in Germany as well as the media. And Case No. 2: The current debate about the proposed U.S. missile shield in Europe has raised a lot of concerns among the European public, particularly in Germany. Another poll of the German newscast “Die Tagesschau” found out that 71% of the German public believes that Russian security concerns — complaining about a U.S. threat in Europe targeting Russian missile sites — are real and Russian concerns are legitimate. Only 21% believe the U.S. government’s explanation that those 10 missiles are only directed against a future Iranian missile threat.

Transatlantic Crisis

To begin with, we need to figure out why there exists a transatlantic crisis and, if so, what brought it on?

Lets start with the most decisive turning point of transatlantic relations: 9/11.

When 9/11 happened — instead of a transatlantic crisis, we experienced an emotional sentimentalism of solidarity and harmony. Let’s remember that Le Monde wrote at the time: We are all Americans. But we also know that this sense of solidarity and commonality with the U.S. was of short duration. Rather than losing themselves in expressions of mourning and grief — as expected and favored by Europeans,especially Germans — the US began to identify and attack the sources of terror. I remember quite clearly the time span between September and December 2001 when it was possible to detect a change in tenor and reporting on both sides of the Atlantic. While U.S. media after 9/11 distinguished themselves by their use of bellicose reporting and choice of words, European media engaged in moralistic appeals to political reason, such as victory through diplomacy and a number of suggestions to turn this problem over to the U.N.

Here are a few examples: In the U.S. one read and heard about the “war against terror” and “preemptive strikes” and “the deployment of forces”, in short, the use and implementation of superior military forces.

In Europe, they played a different tune:” Give diplomacy a chance”, “strengthen multilateral institutions”, caution against single-handed engagement, etc., etc.

I have no interest in doling out blame to one side or another but it is certain that this incendiary atmosphere and the difference in approaches — reflected in the reporting styles of the media — played a significant role in deepening the gulf between Europe and the U.S. Aside from this, it is undeniable that both sides committed significant political and diplomatic gaffes. And let’s not forget, Europeans went their different ways early on rather than trying to reach a unified political consensus.

France and Germany — with a view to the populist leanings of their countrymen — decided to take singular political positions and made it clear that they wouldn’t support military action against Iraq and Afghanistan even if the U.N. were to agree to international military intervention.

That fact alone exposed the military threat card against Saddam Hussein as a paper tiger while, on the other hand, the Pentagon and Don Rumsfeld were convinced they could wage this war by themselves. The concept of “the coalition of the willing” was coined and the U.S. president appeared to be quite prepared, if necessary, to unleash America’s superior military forces against the “identified enemy”, Saddam Hussein.

It is amazing, but if one were to research the causes and preparations for the Iraq war, it would very quickly become obvious that the network of international alliances and mutual consultations completely failed on both sides of the Atlantic. And not only because the intelligence community and the media gave wrong accounts about potential weapons of mass destruction — again, not only on this side of the Atlantic — but also because domestic concerns and power plays overrode and dominated rationality in questions of foreign policy much of the time.

To be specific: In autumn of 2002, I attended a memorable presentation at Harvard University as well as here in Washington, hosted by Marvin Kalb and the Shorenstein Center. At the time, the subject was the European point of view vis-à-vis the Iraq conflict, the invited guests were print and electronic media journalists. Among others, on the dais, there was a representative of “La Stampa”, a journalist of the “Guardian”, a foreign policy commentator of “Le Figaro” and the representative of “El Pais”. Despite the fact that there were considerable differences of opinion among us regarding U.S. foreign policy, we were surprised to find during the discussion that we — meaning, on-site correspondents sent here to report on U.S. policies and the underlying reasons thereto — were neither heard nor printed by our editorial departments.

The reason: domestic policy commentators had taken the lead in our head-quarters. They wrote the commentary and they interpreted for their constituencies how to view the United States. This means, in effect, that domestic prejudices were tended to by domestic commentators and the U.S.’s foreign policy as well as the foreign policy of their own country were viewed entirely from the perspective of domestic concerns and necessities.

And that means, Ladies and Gentlemen, that we as correspondents who’s job it is to build bridges, to analyze events requiring explanations for our countrymen at home in order to make them more accessible, were simply ignored. Our analytic bridge-building skills weren’t needed anymore, in fact, these bridges had long ago been dismantled. And this, Ladies and Gentlemen, is also one of the reasons for the transatlantic crisis in which are currently mired.

But worse was to come: When sage and sane voices attempted to inject a measure of clarity and objectivity into the heated emotional debate, they were shouted down and hounded. I was completely unfamiliar with the concept of “hatemail” until the onset of the Iraq war; it is now a commonly used expression. Let me tell you about a case in point: a highly respected colleague of mine, the foreign policy editor in chief of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), a newspaper normally considered by its readership to be U.S.-friendly and pro- transatlantically inclined, told me that after several articles in which he attempted to show the arguments presented by both sides in support of their particular foreign policy justifications and actions, he received volumes of personally abusive letter and hatemail. Some went so far as to include death threats and foul personal insults. To his mind — as well as to my mind — this hadn’t happened in Germany up to now. Not even during the NATO “missile crisis “and Reagan’s Star Wars program.And now I will definitively answer the initially posed question: Is there a transatlantic crisis? The answer is an unqualified “yes” and this crisis goes deeper and has lasted far longer than most of us want to admit. This means that there is no point in hoping this crisis will go away on its own, as many in the aging generation of transatlantic supporters as well as professional diplomats would prefer. We have to accept and confront this crisis and try to find ways to deal with it.

However, it is also true that there have been many tests, crises and ups and downs in transatlantic relations over the years. To name just a few: the conflicts concerning the multilateral force (MLF) in the 50’s, the conflict concerning “burden sharing” within the NATO alliance in the 60’s and 70’s and the deeply rooted political rejection of the Vietam War during the same period, and the missile debate in the 80’s and 90’s as well as the deployment of Pershing missiles in Europe that led to the green movement.

What’s different this time around are the strident tones as well as the dramatic rise in anti-Americanism which has found a heretofore unparalleled acceptance among the population. Today, more than of 2/3 of Germans are either very critical of the U.S. or clearly anti-American in their attitude. The acceptance ratio of the U.S. has dropped from above 70% to below 30% within in three short years. This has not always been the case. During the height of German-American relations, there was no closer ally in the world. The reasons for this were historical as well as factual. To mention just a few:

- an existing common threat.

- a common sharing of interests, from economic interests to values and political concepts, all the way to

- the unrestrained copying of the American way of life in Western Europe, foremost in Germany

America was seen as a role model, the gold standard whose way of life and affluence was to be copied at all costs. From washing machines to cars and refrigerators, from Coca-Cola and Rock ‘n Roll to pettycoats, Europe became a carbon copy of the American culture of consumption.

Behind this “seeming unity of interests” there was the simple wish to be a part of this affluent prosperity and to achieve a freer, democratically shaped lifestyle. I will venture the theory that we didn’t really understand Americans even in those heady days. We wanted to focus on the things we had in common, the positive side of all this. Everything that might separate us, or that was strange or unfamiliar, didn’t exist or wasn’t allowed to come to the surface.

In retrospect, let me try to give you a sense of the media in those days: I distinctly remember the reports coming from older colleagues who shaped our picture of America. They were interesting, mostly positive stories accompanied by photographs, tales of adventures, thrilling reports which didn’t overlook the negative but put everything into an overall positive context. A “clash of cultures” or the affirmation of domestic prejudices — which most likely existed even then — didn’t happen. As it turns out, even then there was much which might have given us pause: the death penalty, the spoiling of the countryside, poverty, homelessness, drug use, excessive abuse of natural resources and, last but not least, the gigantic U.S. atomic/nuclear industry including the Harrisburg fiasco.

And what about today? These days, many of my German friends — who have endured years of negative media coverage concerning the United States — wonder how I can bear to live with my family in the U.S. under Bush? Their image of this country runs the gamut from soft faschism to a more virulent form thereof, from a repressive police state to the periodically dramatic suspension of citizen’s civil rights. What they don’t mention is that Americans are still not required to carry identity cards nor forced to adhere to compulsory registration requirements and that it is possible to live as freely and unfettered in this country — once one is actually in it — as few other places in this world can rival. This distorted view held by Germans/Europeans does not reflect reality.

With Bush at the helm, does the United States have even a fighting chance to improve its miserable image in Germany and Europe? The answer is a flat “No”.

Values and Values

After the 2004 election, Senator Joseph Liebermann correctly emphasized that one of the decisive reasons for the devastating election results of the democrats was a problem with “values”. According to Liebermann, Democrats are considered the anti-war party. That makes them “the good guys” in Europe but at the same time was a significant factor in their election defeat since the majority of Americans considered themselves to be a nation at war and voted correspondingly. And let’s not forget the clash of values between the GOP and the Democrats concerning gay marriage, legal abortion, stem cell research and what is taught in schools.

But, for the moment, let’s stay with the question of war and peace and the differing attitudes on both sides of the Atlantic. A while ago, Kagan published a small booklet] that caused a bit of an uproar. His theory was that: Europeans are from Venus and Americans are from Mars. Specifically, this implies that the U.S. tends to be more prepared to solve its political objectives by force than are Europeans. This theory might be exaggerated but,even if so, this exaggeration contains the proverbial “kernel of truth”, at least according to Theodor Adorno.

I would agree with this assessment : In my estimation, this is the major point of dissent — the willingness to solve conflicts through the use of force is not the same on either side of the Atlantic.

Obviously, this has something to do with the course of history and the lessons learned thereof . First, let’s take a look at Europe: Two World Wars didn’t just ravage Europe but they also led to the realization that war — as Clausewitz put it — as a “continuation of politics through other means” wasn’t working any longer. As a result, the European Union was conceived, a secular federation of civil societies, that tries to solve its problems through negotiating and diplomacy.

Threat scenarios in Europe are perceived as such but tend to be treated as peripheral. This means that individuals may be [feel?] threatened but not entire populations. Here in the U.S., we have the exact opposite approach: threats are perceived as directed at the society as a whole, or the American way of life, or individual liberties or the much-loved Constitution — in other words, everything that is considered “American”. It is for those reasons that 9/11 and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are a watershed in German/European relations with the U.S.

But there is another difference worth mentioning: While we were confronted with with a wave of, at times, excessive patriotism before and during the Iraq War — something conceded even by the U.S. media by now — we have to contrast the image of a U.S. society, united by a common threat and, in response, acting-as-one, with that of Europe which consists of an assembly of secular, permissive and highly individualized societies with an emphasis on group interests and particularism.

And what about the media? In my estimation, they are increasingly losing their traditional role as mediators, of being the analytical and factual brokers of information. Confrontational infotainment has taken over as the popular favorite which, based on market research, will hew to the lowest common denominator, in other words “give the public what it wants”.

About 30 years ago, when I began my career in Hamburg as military correspon-dent for Der Spiegel, we were proud to adapt as our journalistic motto the one used by the New York Times: All the news that fit to print! This was our guiding star when we researched stories, which were then verified by further research in archives and the like, and then — and only then — printed. Nowadays, the motto for print as well as electronic media seems to be: All the news that’s fit to sell!

No wonder then, that the mega-media concerns in the U.S. today are owned and dominated by Disney World, General Electric and in Germany increasingly by foreign financial conglomerates with a view towards profit. This profit-driven competition is squeezing out serious news coverage and claiming serious journalism as one of its victims. The privatization and commercialization of the media — with Europe having caught up to the American way in the last 20 years — did lead to a disproportionate rise in the salaries of journalists, particularly those in the electronic media. This must surely have sweetened the leave-taking from serious journalism for a number of my colleagues. Others,frustrated with the new profit -only-regime have retreated to the academic world.

One can lament this commercialization that has contributed to the considerably lower ethical and professional standards. Just think of the plagiarism scandal at the New York Times, fraudulently obtained Pulitzer prizes, invented interviews and stories that have confronted us in the last several years.

The fact remains that the media has become a sounding board and amplifier of public opinion and populist trends. The mission to inform, the focus on presenting differences of thinking and opinion — including to be a part of the dissemination of culture and knowledge — is among the missing. In closing, allow me a few comments concerning transatlantic relations.

- Transatlantic relations have changed. Today, anyone trying to enhance their political career by invoking the mantra of our commonly shared values and the unbreakable bonds of friendship over the last 50 years, is not operating in the real world. The unbreakable friendship is a thing of the past: common or contrasting interests define the political landscape of today. And yet, there are the positive common achievements: prosperity for Western Europe, maintaining freedom, the German reunification and the end of communism are tangible, positive results.

- Concerning the future, Europe will have to define its own interests in a pragmatic and analytical way. So far, the outline of a common European foreign policy towards the U.S. and the world is barely noticeable. In the past 10 years, we were mostly occupied with putting our own internal house in order and didn’t have the time to look far beyond that. The war in Afghanistan and against terrorism changed all that and we will have to come up with our own position vis-à-vis the war in Iraq as well. NATO’s position to accept the mandate of being part of the security force in Iraq, can be seen as the beginning of a European position in that direction.

- What we need to avoid: Anyone trying to unite Europe so that it can function as a counterweight to the U.S. will fail, at least in my estimation. France never tried to conceal that it considered that to be the pre-eminent objective of the “Grand Nation” as witnessed by the congratulatory message from Chirac to Bush combined with the call to Europeans to show even more unity, indicates clearly the path that was intended. Maybe this is going to change under Sarkozy, who seems to be more transatlantic and pro-american oriented than all his predecessors.

- If Europe needs the common enmity against the U.S. in order to present a united front or, to put it another way, as the “glue” to find its own identity, that would be proof of the tenuousness of our own values and commonalities. Our motto should be: Emancipation from America — YES, Emancipation against America — NO THANKS.

- But there is hope: we still have more in common then what devides us. This is especially true in the areas of trade and commerce.The new transatlantic partnership initiative of the German Chancellor Merkel will be a litmus test for both of us in our continuing commitment to free trade and shared interests! And finally, a last word concerning the media: they ought to revert back to their original role as neutral observers and disseminators of information. To my mind, we neither need media with the moralizing claim of the “Preceptor Germaniae” nor do we need the American media functioning as cash-cows for a trash-culture, disseminating news only under the mantle of sensationalist or sales considerations. Perhaps this wish is too utopian or too old-fashioned and conservative to have any chance of coming true. However, I will not — can not — abandon my hope for enlightenment, for that spark in the human consciousness.

Thank you for listening.