STORYS & ARTICLES

RIAS Berlin and the Americans

by Prof. Herbert Kundler, former Program Director RIAS Berlin

When the American forces left Berlin in 1994, after almost 50 years, the memory of the radio station they founded remained. RIAS (Radio in the American Sector) is an example of successful German-American cooperation. Its success was anchored in a number of factors: the high public regard it enjoyed, its incomparable journalistic effectiveness in the crisis period of the Cold War and the collapse of communism, and its audience of millions of Berliners and citizens of the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

RIAS offered a broad-based range of programmes: news bulletins, entertainment, programmes that dealt with the problems and interests of listeners in Berlin and the “zone” (subsequently the GDR), a comprehensive cultural programme, ranging from the classics and the “University of the Ether,” to radio plays and Friedrich Luft’s theatre review the “Stimme der Kritik” (The critic’s voice), successful light entertainment programmes with groups such as “Die Insulaner,” quiz shows and rock music. But none of these programmes would have been possible without the second guideline, which was anchored in the American constitution and which guaranteed freedom of the press in matters of programming.

But RIAS was more than just a journalistic or artistic medium. It was a forum for self-confident German democrats such as Ernst Reuter, Jakob Kaiser and many more like them. It was a channel for writers suffering political suppression, it was a sponsor of the Berlin music scene that had to be reconstructed after the War, and it was a channel of mediation for the younger generation who were not marred by the dictatorships of the past.

RIAS’ first mobile broad-casting van, 1946

Mayor Otto Suhr (right) presents a model of the Liberty Bell to Gordon Ewing, RIAS director, 1953–1957.

RIAS director Robert Lochner and General Lucius Clay visit RIAS.

It had become second nature to all the Americans who worked for RIAS whether they had been born in the United States or had emigrated from Europe, whether they were professional diplomats or former journalists that intervention of any kind in their journalism would not be tolerated. Any outside intervention would have compromised the integrity of the station. How could the radio station have otherwise called itself “The free voice of the free world” ? It was clear that critical reporting and open discussion were needed in order to create freedom in their own political and social environment.

The open and liberal views of the “RIAS Americans” spilled over onto the other media. When Ludwig von Hammerstein, who had previously been director of Norddeutscher Rundfunk for twelve years, applied for the post of director of RIAS (which he held from 1974-1984), he talked to the Chairman Gerard M. Cort. Cort showed him a statute of 1973, which stated that the advisory board was planning to introduce mandatory guidelines for broadcasting policy. Hammerstein said of the discussion:

“My past experience with advisory boards has not always been pleasant, so I immediately asked about these guidelines. I said I needed more information about this point in order to make my decision. Cort laughed and said that no such guidelines actually existed and that furthermore he had no intention of drafting any. He said that everyone who worked for RIAS followed fair, tried-and-tested journalistic rules. That is the only way to produce good broadcasting.”

In June 1953, the mutual trust between Germans and Americans was further intensified: Germans who had worked for years with RIAS protested publicly and threatened strike action when RIAS director Gordon Ewing was summoned to appear before U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Committee for Anti-American Activities. In view of the fact that RIAS’s broadcasts had played a decisive role in the popular uprising that had taken place in East Germany shortly before, on 17 June 1953, the accusation against Ewing of alleged pro-Communist activities seemed positively grotesque. Many foreign media, such as the New York Times and the BBC, reported the protests of the German employees. In the end, the U.S. Foreign Ministry retracted Ewing’s summons (on the grounds that there were no funds to pay for the flight to Washington). In view of Ewing’s possibly imminent departure from Berlin, Governing Mayor Otto Suhr personally presented Ewing with a miniature replica in silver of the Liberty Bell.

Although RIAS was a department of the United States Information Agency (USIA), it worked without official American “monitoring” That was to some extent thanks to American Pulitzer Prize winner Edward R. Murrow, who was head of USIA from 1961 to 1963, and whose firm belief in the great importance of the free press in a democracy was an integral part of how he exercised his office. In 1961, on RIAS’s fifteenth anniversary, Murrow stressed, as several presidents, secretaries of state and American ambassadors would do in the years that followed, that RIAS was a symbol of the presence of the Americans in Berlin and of their steadfast determination. At the same time, he emphasised his confidence in the people working for RIAS and in their ability to fulfil their remit to provide impartial and unprejudiced information to Berlin’s isolated population.

RIAS also owes a special debt of gratitude to General Lucius Clay. Famous as the “Father of the Berlin Airlift,” Clay launched a donation appeal in the United States in which many Americans gave money to buy a replica of the Liberty Bell for the citizens of Berlin. On 24 October 1950, United Nations Day, the bell was rung for the first time. From this day on, its chimes could be heard on RIAS every Sunday afternoon.

When Germany was reunified and Berlin’s four-power status was rescinded, RIAS’s status as a department of USIA also changed. Parts of RIAS became Deutschlandradio, broadcasting programmes about Germany overseas, and RIAS 2 was privatised and became R.S.2. Of the “old” German-American RIAS, which Willy Brandt and other leading politicians, prominent artists and Members of the Senate had called an essential part of the post-war years, only a vestige remains. The name RIAS lives on in the RIAS Berlin Commission, which was founded by the American and German governments and which primarily funds exchange programmes for young journalists.

In the course of three decades, 89 Americans worked for RIAS. Their areas of work were many and varied: some were in the administration, others worked on the creative side of things and played a decisive role in programming. During these years, RIAS had a total of 15 American chairpersons. But the “RIAS Americans” and their colleagues in Bonn and Washington wanted to do more than just run a credible radio station; above all, they helped West Berlin to survive and helped pave the path to freedom for those Germans who were politically oppressed.

Over thirty years ago, Willy Brandt, Governing Mayor of Berlin at the time, described RIAS and German-American relations in the following words that are still relevant today:

“With the help of an army of occupation, a radio station has been set up in an occupied city. Coincidence or fate has brought people together who are running an independent radio station, but they have neither been officially appointed to do so nor is their responsibility clearly defined in law. They are working first and foremost according to the dictates of their convictions and the unwritten laws of their conscience. I find it marvellous that under these circumstances, in which many people in West Germany are unable to think of anything beyond their own local problems, this radio station has been able to develop into a political institution within the first few years of its life. By virtue of its hard work and despite the difficulties, RIAS has become a proper broadcasting corporation and also a link between the people of this divided country.

The Americans and Germans who built up the radio station came from different psychological starting points. This is an excellent example of German-American cooperation, a visible sign of the congruence between German and American interests. In our relations with America, we must always be open and prove our solidarity. With friends, it is not necessary to constantly show gratitude. What we owe America cannot be expressed in figures. If we continue to work together and trust one another, we will pass whatever tests the future may hold in store for us.”

Unintended Consequences: RIAS and the Cold War

by Prof. Howard S. Pactor, University of Florida, Gainesville

In the winter of 1945–46, the once-great city of Berlin was beginning its long climb from the ruin of war. Under terms of the Yalta Agreement, Germany had been divided among the three victorious Allies with an area assigned to the French taken from the American Zone of Occupation in western Germany. Similarly, Berlin was divided into four sectors for each of the occupying powers. With the general suspicion and mistrust among the occupiers, some semblance of normal life resumed in Berlin.

Among the assets of the Third Reich seized by the Red Army was Radio Berlin with its studios in the British sector and its powerful transmitter at Tegel in the French sector. The Soviet forces quickly put the radio back into service, even using former Nazi staff members, to present the Soviet message to the people of Berlin and in its Zone of Occupation. Its broadcasts were as effusive in praise of its efforts to reconstruct its occupation zone and equally as mendacious in its reports of problems in the reconstruction in the western zone. Because there were no other radio facilities in Berlin, the Western Allies hoped to secure time — an hour a day for each Western power — on Radio Berlin for broadcasting to residents of their zones. Following protracted negotiations, it became apparent that the Soviets would not grant the Allies any access to Radio Berlin; as a result, the United States decided to create a broadcast facility of it its own. In his 1961 doctoral dissertation, Donald R. Browne suggests that “it is interesting to speculate on the supposition that, for the Russian intransigence in the early days of the occupation of Berlin, there would never have been a RIAS.

In creating its own broadcast presence in Berlin, the American Military Government set on course a radio operation that would do much more than intended-simply announcing information from the military authorities to the German residents of Berlin. The unintended consequences were that the radio station would become a leading source of culture, education, political enlightenment for those in West Berlin and a political instrument in dealing with the Communists-both Soviet and German-in the what was to become the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

In creating its own broadcast presence in Berlin, the American Military Government set on course a radio operation that would do much more than intended-simply announcing information from the military authorities to the German residents of Berlin. The unintended consequences were that the radio station would become a leading source of culture, education, political enlightenment for those in West Berlin and a political instrument in dealing with the Communists-both Soviet and German-in the what was to become the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

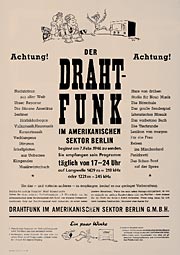

Finally giving up in its attempt to obtain time on Radio Berlin, the American Military Government resorted to a method of broadcasting familiar to the German public — Drahtfunk — or wired radio, which had been used by the Nazi regime. On November 21, 1945, the Americans ordered the re-opening the system and hiring the necessary personnel to operate the station. The system was first known as DIAS-Drahtfunk In the American Sector — and utilized the telephone system, or that portion of it in the American Sector that still worked, for its wire. It began operation on February 7, 1946, at five o’clock in the evening; following the announcement of the service, the first program to be heard was American jazz. The staff consisted of four Americans as supervisors and about 80 Germans as the operational staff.

Finally giving up in its attempt to obtain time on Radio Berlin, the American Military Government resorted to a method of broadcasting familiar to the German public — Drahtfunk — or wired radio, which had been used by the Nazi regime. On November 21, 1945, the Americans ordered the re-opening the system and hiring the necessary personnel to operate the station. The system was first known as DIAS-Drahtfunk In the American Sector — and utilized the telephone system, or that portion of it in the American Sector that still worked, for its wire. It began operation on February 7, 1946, at five o’clock in the evening; following the announcement of the service, the first program to be heard was American jazz. The staff consisted of four Americans as supervisors and about 80 Germans as the operational staff.

The facilities were in the telephone exchange building in the American Sector, but the Military Government gave the station little help in the way of equipment. The lack of attention by the military government may have been something of a blessing as it allowed the staff to solve problems and gain experience in making do with little direct supervision or support; it also allowed the broadcasts to be made in German. This creativity would be useful in developing ways of providing information for residents of East Berlin and the GDR.

The facilities were in the telephone exchange building in the American Sector, but the Military Government gave the station little help in the way of equipment. The lack of attention by the military government may have been something of a blessing as it allowed the staff to solve problems and gain experience in making do with little direct supervision or support; it also allowed the broadcasts to be made in German. This creativity would be useful in developing ways of providing information for residents of East Berlin and the GDR.

While DIAS was a start, it was not what was needed. The system had too many technical problems, including too few civilian telephones, which provided access to the signal, and poor signal quality. A major problem was in the telephone cables, which had been contaminated by water seepage resulting from the heavy Allied bombing of Berlin. Over the next few months the DIAS staff improved its signal and increased its hours of programming. Still, it was not enough; broadcast radio, not wired radio, was the answer. By the fall of 1946, after slightly more than five months of wired service, the technical staff at DIAS had located and acquired a low-power radio transmitter and on September 5, 1946, began broadcasting even though the 800-watt transmitter could not provide coverage of all of Berlin. DIAS, soon to be called RIAS-Rundfunk [Radio] In the American Sector-signed on the air with the usual announcement of intent at three o’clock in the afternoon; its first musical selections were Melodien von Jerome Kern. One can only speculate on the irony of the choice of music — songs by a Jewish-American composer being performed in Hitler’s capital.

Unintended Consequences: Music

Because American military regulation forbade the employment of former Nazis who worked for Goebbel’s Radio Berlin, the RIAS staff was less skilled in preparing and broadcasting radio programs. Still, the station developed an ambitious program for growth and service. In keeping with the German love of music, RIAS created a number of music groups; just two days after it began broadcasting, the RIAS Symphony Orchestra gave its first concert. Once again, Germans could hear the music of Jewish composers — Mendelssohn, Offenbach and Mahler — who had been banned during the Nazi years. Over the years, RIAS created choral groups, chamber ensembles, a youth orchestra, and dance bands. The music groups issued an impressive number of recordings that are still sought by collectors. The RIAS dance bands were among the most popular musical groups in Western Europe in the 1950s and ’60s. Among the popular music performers on RIAS broadcasts who were familiar to Americans were Marlene Dietrich, Werner Müller, Horst Jankowski and Catharina Valente. The creation of these music groups, along with RIAS-sponsored public concerts, provided a much-needed lift in the morale of Berliners who were soon to be an isolated by the Soviet-imposed Berlin Blockade.

RIAS’ musical programming provided employment for a large number of musicians who might otherwise have lingered without work or turned to the Soviet-backed East Germans who were spending money to preserve the German cultural heritage. Perhaps a more important unintended consequence of the late-night musical offerings of RIAS resulted from playing American jazz and rock ’n’ roll-two forms of music noted for their freedom. The appeal of these kinds of music to young Germans in the GDR kept alive a notion of free expression and was a welcome alternative to the controlled offerings of stations in the East. Although RIAS received thousands of letters per month, no attempt was made to sample listeners’ preferences until 1951. In July of that year, the Office of the U.S. High Commissioner undertook a survey of listeners.

This was difficult to implement, since the people conducting the survey had to interview their ’subjects’ when the latter crossed into West Germany or West Berlin on business… The subjects were not refugees — they were returning to their homes-and, therefore, many of them were reluctant to be interviewed. Out of the approximately five hundred who were interviewed, these findings were noted: 81 per cent of the sample listened, mainly to RIAS, and 68 per cent of the sample named RIAS ’best-liked’ station, chiefly because of its truthfulness… Most interesting programs on RIAS were news, 42 per cent; … ; music, 22 per cent… RIAS was named by 83 per cent as the station most often listened to for news.

Still, it was dangerous for East Germans to listen to RIAS. In September of 1950, a resident of Dresden was sentenced to 18 months in jail for writing to RIAS, even though the GDR constitution permitted such activity. Although people and businesses throughout the east had been warned, a radio dealer in the state of Saxony was found guilty of tuning to RIAS; his excuse, people wanted to hear good music.

Unintended Consequences: Education

Like most of the infrastructure in Berlin following the war, the public schools were a shambles. Although radio broadcasts for schools were virtually unknown in Germany, RIAS began Schulfunk- broadcasts for schools-soon after the operation switched from wired to broadcast service. With the poor state of transportation in the rural areas around Berlin, particularly in the winter months, Schulfunk broadcasts became an important adjunct to the school system. In addition to the school broadcasts, RIAS devised a program to help teach children, and adults who might listen, how democracy worked. The station, in cooperation with the Berlin school system, created Schulfunkparlament, a parliament for students much like student government in American schools. Each school elected two students to attend monthly sessions of the parliament, which were broadcasts live over the station. Officials of the Berlin city government attended the meetings and were sometimes put on the spot by the children’s questions. By 1951, more than 135 schools were using the Schulfunk broadcasts to supplement education for about 400,000 students, although it took some time for German teachers to adapt to the new teaching tool.

The school broadcasts helped the badly damaged school system cope with teaching students under the primitive conditions of post-war Berlin when school buildings and the transportation system were in ruins. The broadcasts also helped train teachers in new methods of teaching; the programs presented alternatives to the traditional rote memorization and strict discipline of traditional German education. The children’s parliament provided instruction in the process of democratic government for youngsters who would become the voters and defenders of the ’Outpost of Democracy’ that Berlin was to become as the decades of the Cold War ran their course. The spill over of these programs, like much of the RIAS programming, added its bit to help residents of the eastern zone to cope with the conditions developing there.

As Communist political influence gained ground in the Humboldt University in the Soviet Sector, students began demanding the establishment of a university free of Communist ideology. In February 1948, RIAS began broadcasting Hochschulfunk (University of the Air) and in its first broadcast took a stand against political influence in the university. The broadcast also discussed the founding of a free university in West Berlin. These discussions were instrumental in the founding the Free University of Berlin, which gained an international reputation during the Cold War — not always a positive reputation as during the student protests of the 1970s.

Unintended Consequences: News and Politics

Of all the activities RIAS was involved in during its 46 years of service, reporting news and political affairs in both West Berlin and the GDR constitute the station’s most widely known activity. And the reputation was well deserved. The approach of municipal elections in October 1946, it was assumed there would be one city government for Berlin. The newly re-invented RIAS was quickly involved in a get-out-the-vote campaign. The station was in the thick of things as it opened its microphones to the political parties contesting the election. Soviet-controlled Radio Berlin, on the other hand, allowed only candidates of the SED, and after some negotiations, candidates of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) on its air. Following the election, RIAS covered the vote counting at the Berlin City Hall and provided complete and impartial reports of the returns. This was the first step in establishing RIAS’ reputation for impartial reporting. In September of 1948, Communist thugs invaded Berlin City hall during a session of the all-Berlin City Council and brought an end to the government. Berliners got a first hand glimpse of Communist methods as a young RIAS reporter, Jürgen Graf, presented a running description of the melee until his microphone was disconnected and he was beaten.

From the beginning, the purpose of RIAS was to inform residents of Berlin; the importance of the spill over, however, was of great benefit to the American Military Government as it countered Radio Berlin propaganda. Of even more importance to German staff of RIAS is that it could reach, influence and help Germans living in the East. Following a meeting with East German youths visiting West Berlin, the U.S. State Department reported that” [T]he one major topic was RIAS itself. Over and over again, one heard how much hope the people of the zone place in RIAS, their only reliable connection with the outside world.“

From the beginning, the purpose of RIAS was to inform residents of Berlin; the importance of the spill over, however, was of great benefit to the American Military Government as it countered Radio Berlin propaganda. Of even more importance to German staff of RIAS is that it could reach, influence and help Germans living in the East. Following a meeting with East German youths visiting West Berlin, the U.S. State Department reported that” [T]he one major topic was RIAS itself. Over and over again, one heard how much hope the people of the zone place in RIAS, their only reliable connection with the outside world.“

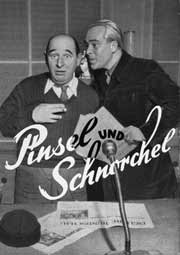

To meet these needs, RIAS instituted a number of programs in 1949 that were of importance to residents in the East. These included “Die Insulaner” („The Islanders” ), a program of satire which remained popular for years; “The Sandman with his Political Tidbit for the Eastern Zone” lampooned political figures in the East, and, in May of 1949, Sendung fur Mittelduetschland (Broadcast for Central Germnay). This program was designed to let East German residents know about events in other regions of the GDR, which would not be reported in the heavily controlled press in the East. In the following year this program was being broadcast three times a day. The title was later changed to Aus der Zone fur die Zone (From the Zone to the Zone) and was a staple of the RIAS schedule for years. This program regularly identified residents of East Germany who reported to East German Security Police [the Stasi] on the activities of their neighbors. Collier’s reported that, “some 300 people from the zone made their way into Berlin and to the RIAS studios, to protest the use of their names on the programs, insisting they weren’t spies… Investigation showed that of these 300, only 50 had been mentioned on the air.“

To meet these needs, RIAS instituted a number of programs in 1949 that were of importance to residents in the East. These included “Die Insulaner” („The Islanders” ), a program of satire which remained popular for years; “The Sandman with his Political Tidbit for the Eastern Zone” lampooned political figures in the East, and, in May of 1949, Sendung fur Mittelduetschland (Broadcast for Central Germnay). This program was designed to let East German residents know about events in other regions of the GDR, which would not be reported in the heavily controlled press in the East. In the following year this program was being broadcast three times a day. The title was later changed to Aus der Zone fur die Zone (From the Zone to the Zone) and was a staple of the RIAS schedule for years. This program regularly identified residents of East Germany who reported to East German Security Police [the Stasi] on the activities of their neighbors. Collier’s reported that, “some 300 people from the zone made their way into Berlin and to the RIAS studios, to protest the use of their names on the programs, insisting they weren’t spies… Investigation showed that of these 300, only 50 had been mentioned on the air.“

The RIAS broadcasts, throughout its 46 years, were an irritant for the East German leaders. The GDR chairman, Wilhelm Pieck, once railed that “RIAS is nothing more than poison! Time and time again, it undermines our efforts to direct the thinking of the people into correct political lines. It makes us look ridiculous!” The vilification of RIAS was on-going and East German/Soviet jamming of the RIAS signal was intense. By the end of 1953, the East Germans were operating at least four or five jamming operations to prevent RIAS’ signal from reaching its intended audience.

Perhaps the most important single event in RIAS’ history, with the world looking on, occurred when workers in East Berlin struck. Early in 1953 the RIAS called for voluntary increase in work norms for all East German workers; RIAS, during this period, provided considerable programming in its broadcast series, “Workday in the Zone” and “Berlin Speaks to the Zone,” about the effects of the decision to increase. In June the East German government ordered a ten-percent increase in the already-impossible work norms in the construction projects along Stalinallee, the showcase apartment blocks being built in the eastern sector. The increase in work norms came on top of salary cuts and other speed-ups resulting in severe decreases in purchasing power of the East German mark.

During the evening of June 15, 1953, RIAS reported that three isolated demonstrations against the increase had occurred; no other news agencies carried the story. Workers had had enough and marched on SED (Communist) Party headquarters with a petition demanding revocation of the latest increase of work norms. The party leadership refused the petition. With the work stoppage and march on the 16th, RIAS began carrying reports of the events at 4:30 that afternoon; a visit by a workers delegation to RIAS was reported by the station on its 6:30 p.m. broadcast and at 7:30 the RIAS broadcast the workers’ demands. These included free, secret elections, lowering the cost of living and the abolition of norms. Acceptance of the demands was not conditional; if the demands were not met by the morning of the 17th, the workers would strike, which they did. More workers in the eastern sector joined in the protest and the SED leaders first used the state security agency to quell the protests. When this failed, the Red Army was called in and the demonstrations became far more violent with shootings, injuries and deaths. Although RIAS was playing a role in a dangerous situation, the station did not involve itself in directing the strike. Basically, it provided a running report of the events and a forum for the workers to air their demands-something they could not do in the controlled media of the Soviet zone.

In effect, RIAS’ broadcasts of the riots served as something of a command post. It passed along information about the locations of the protesters in Berlin, explaining problems and demands, reporting the results of negotiation and, through its information sources in the GDR, acted as a catalyst for protests in other East German cities. Support for the workers’ demands and protests were recorded in more than 270 cities and towns in the East Zone. RIAS avoided direct involvement in the riots, but it was perilously close to involvement. “Without RIAS, the zone would not have learned about the strike [in Berlin] for days, and the national insurrection might never have taken place.“

Although RIAS was perhaps more deeply involved in the events of June 17th than many observers would have liked, the events in the East did involve, and even threaten the safety and well-being of fellow Germans, the emotional connections were far too great for the station to ignore. In the long term, the broadcasts of the events in June, and the programming both before and after the event, firmly established RIAS in the hearts of Berliners and those who lived in the GDR. Listeners in the East knew there was a free source of news and information, no matter how dangerous it might be to listen to the broadcasts.

Still, the events of June 1953, and the much more violent Hungarian Revolution in 1956, revealed to residents of the eastern Soviet satellite states that the West would not intervene militarily in their internal affairs. This attitude was made even more apparent with the Berlin Crisis of 1961, which resulted in the infamous Berlin Wall, the symbol of political repression for nearly three decades.

Surveys taken during the GDR times supported the notion that the East-West division of German was a permanent condition. By 1968, only 13 per cent of West Germans thought the two Germanys would ever be reunited; by 1987, just two years before the end of the GDR, only three per cent of those polled thought reunification would occur within the foreseeable future. Chancellor Willi Brandt’s policy of Ostpolitik in 1969–70, the West’s policy of détente with the Soviet Union and, perhaps, the weariness resulting from so many years of Cold War, may have led many — Germans, West Europeans and Americans – to adopt an attitude of cooperation with the GDR because the balance of power seemed to be making the East-West split a permanent feature of the world’s political landscape.

Unintended Consequences: Two Ends

Following the Four Powers Agreement of 1972, the confrontational flash point that was Berlin receded. The two halves of the great city went their separate ways in a ’business as usual’ manner. Jürgen Graf, editor-in-chief of RIAS, news noted THE big confrontation was kind of over. For a journalist who was so much involved from 1945 to 1963 after the Kennedy visit, it was in a way boring. It was routine. The questions now debated were of the type whether women over 65 can cross now or in two years.

Following the Four Powers Agreement of 1972, the confrontational flash point that was Berlin receded. The two halves of the great city went their separate ways in a ’business as usual’ manner. Jürgen Graf, editor-in-chief of RIAS, news noted THE big confrontation was kind of over. For a journalist who was so much involved from 1945 to 1963 after the Kennedy visit, it was in a way boring. It was routine. The questions now debated were of the type whether women over 65 can cross now or in two years.

In some ways RIAS’ glory days were over, but, still, the information, news and music continued to have their effect on the minds of those who were behind the Wall. RIAS was, perhaps, a minor player as the Soviet Union under Gorbachev loosened its grip on its satellites. During the summer of 1989, residents of the GDR abandoned homes and jobs to escape through Czechoslovakia and Austria to the West. By November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall came down; the East German government lingered, but its days were numbered, and it, too, ended, disappearing into history. With the end of the GDR, RIAS, too, disappeared from the air. It was officially dissolved on May 19, 1992, the announcement buried on page 13 of the New York Times. The facilities of RIAS continue in operation; radio is now DeutschlandRadio and the RIAS television operation is now part of Deutsche Welle.

Now known as the RIAS BERLIN KOMMISSION, RIAS lives on in the same building in Berlin from which it broadcast for more than forty years. Its contemporary mission is to conduct exchange programs for American and German broadcast journalists, support production of radio and television programs on topics of interest to German and American audiences and to award prizes for radio and television programs and news pieces about German-American topics.

Historic RIAS sign taken off building for repairs – but back now

On May 7, 2009, the historic RIAS sign was returned to the top of the RIAS Funkhaus (broadcast building). It had been removed on March 16, 2009 for urgently required repairs.

Only two years after starting to broadcast on February 7, 1946, the “Rundfunk im Amerikanischen Sektor” (RIAS) had moved into the RIAS Funkhaus and began its broadcast under the well-known RIAS sign on top of the roof. From July 6, 1948, to December 31, 1993, the building was home to legendary RIAS Berlin, also known as “a free voice of the free world” to millions of listeners in former communist East Germany. After the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, and the German Unification on October 3, 1990, RIAS was transformed into the public German radio station DeutschlandRadio Kultur at the end of 1993.

The RIAS sign — put under landmark status about a decade ago — still reminds today’s passers-by of the glorious times of RIAS Berlin as a renown radio station in Berlin during the Cold War.