ONE-WEEK GERMANY PROGRAM 2014

Special Berlin Short Program 2014

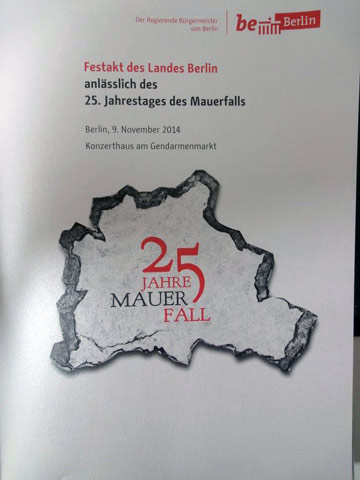

SPECIAL Berlin PROGRAM: 25TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FALL OF THE BERLIN WALL

November 6–10, 2014

Special Berlin Program for U.S. news editors and -directors on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, leading to German Unifaction on October 3, 1990.

1989

The Fall of the Wall —

RIAS reporters on location.

Eight U.S. journalists will have the opportunity to talk to eye witnesses, politicians, historians, and German journalists about the fall of the wall and the following German unification with all its chances and challenges. Back then, there was talk about a so-called “peace dividend” after the end of the East-West confrontation — today the world looks even more dangerous and unstable than 25 years ago.

The participants will visit original sites as well as current exhibitions of the wall.

As a highlight of the trip, the participants will be invited to attend the official Berlin ceremony on November 9, 2014 at Konzerthaus Gendarmenmarkt. There will also be time to experience the public festivities in front of Brandenburg Gate culminating in the release of thousands of balloons marking the former dividing course of the wall.

INFORMATIVE VIDEOS, IMAGES, AND WEBSITE LINKS

Facebook Page “Fall of the Wall”

Facebook Video “Lichtgrenze”

Official Berlin Website “Fall of the Wall 25”

PARTICIPANTS & REPORTS

Kassie Bracken, The New York Times, New York, NY

I was standing in front of the Berlin Wall Memorial, gazing at dozens of black and white images — the men and women killed while attempting to cross “no man’s land” — when one photo made me gasp and brought tears to my eyes. Most of the casualties of the wall had been young men in their 20s, but this was a photograph of an infant. I felt an aching sadness as I tried to imagine the sense of desperation felt by two young parents in East Berlin in the 1970s.

On November 9, 1989, I was a 14 year old high-school freshman in Long Island, New York. In the family den, the tv images from Berlin resembled an outdoor rock concert with a crumbling concrete wall for a stage. Those joyous sights and sounds underscored what would long be my understanding of what reunification meant to Germany and its citizens: Mauerfall was Europe’s celebration of the decade and the East would now reap the benefits of liberation.

25 years later, I joined seven other American journalists in Berlin for a special exchange program with RIAS Kommission in celebration of the anniversary of the event. During four extraordinary days as RIAS Fellows, we met with current and former diplomats, government leaders, political activists, journalists, and artists to discuss the impact of the fall of the wall and the past and present global implications of reunification.

Prior to the fellowship, my sole experience in Germany had consisted of a 48-hour layover in Berlin in 2006. The country was playing World Cup host, but even apart from the football fervor, Berlin teemed with a unique dynamism. During my brief visit, I perceived what I can only describe as a palpable interplay between residual shame and contemporary pride.

It was too short a time to experience such a vibrant city, and I found myself eager to return.

I could not have asked for a better opportunity than the one offered by the RIAS Commission. Our itinerary packed an informative and evocative series of events and meetings around the city.

The diverse line-up of speakers, including the former mayor of Berlin, an ex-Stasi prisoner, an East Side Gallery artist, collectively revealed that what followed the chaotic events of November 9, 1989 was a reunification process that was anything but perfect.

Impromptu conversations with Germans we met along the way echoed this idea. One such encounter occurred while touring the gigantic 360-degree panoramic art installation called “The Wall.” The artist, Yadegar Asisi had spent years creating the piece, a painstaking recreation of East Berlin as seen from the western perimeter of the wall. It was an impressive feat, each small detail giving the viewer a visceral sense of life under communist rule, as well as what it must have been like to have lived in the West, only yards away from the divide.

And yet, when we began to ask about his own personal experiences, our 30-something tour guide described a relatively happy childhood in East Berlin, as well as his memory of excitedly spending the first of his 100 mark stipend post-reunification on a He-Man figurine. For this man, memories of East Berlin were more positive than negative, and reunification meant, among other things, finally getting to taste a pineapple.

But a less sanguine picture was presented the next night by another former East Berliner. After a wonderfully informative dinner with the former mayor of Berlin, Eberhard Diepgen, a few of us stayed behind to talk to his interpreter, Hartmut Voigt. As an adolescent in East Berlin, he experienced the paranoia of always being followed, and described becoming an adult under the watch of the Staasi. He recalled listening to broadcasts from RIAS — Radio in the American Sector — and imagining a life beyond the wall. And yet, once freedom came, Mr. Voigt found it to be a more complicated reality than expected. While reunification brought him opportunity, he saw family members lose jobs and sense of identity.

I felt this sense of ambivalence in the nuanced work of Kani Alavi through his contribution to the East Side Gallery. Mr. Alavi is an Iranian-born painter whose apartment window in West Berlin offered the perfect vantage of the wall during the events of November 9, 1989. His work, Es geschah im November (It happened in November) appears among other commissioned work along the largest surviving piece of the wall. The mural is comprised of many faces, based on his memory of the expressions of East Berliners as they crossed into West Berlin, yet the mood of the piece is not one of joy, but ambivalence. Looking at the many faces, with open mouths and wide eyes — reminiscent of the image in “The Scream” — it was hard to discern whether the expressions were those of joy or fear.

One of the most memorable moments of the trip occurred during a walk back to our hotel after dinner. Shivering in the chilly night air, we encountered hundreds of people standing outside the Brandenburg Gate. All eyes were focused on the giant screen projecting a documentary of the wall’s construction and eventual destruction. As the film came to a close, I expected cheers from the crowd. Instead, amidst silence, I looked around and saw falling tears and quiet embraces.

But while these experiences and collective narratives served to complicate my understanding of the legacy of reunification, the perspectives offered by diplomats Karsten Voigt and Thomas Miller, as well as journalists Erik Kirschbaum and Thomas Habicht crystallized for me Germany’s present and future challenges. Specifically their insights revealed that despite the great strides taken by Germany to become an economic leader and powerful force in the European Union, the pivotal role comes with intense geopolitical challenges, both within the EU, as well as with Russia and the United States.

And yet, as we walked around Berlin, the string of white balloons tracing where the wall once stood provided a constant reminder: this was a time of celebration for the city and we were fortunate to be part of the party. Our trip came to a dynamic close as guests during the state celebration at the Konzerthaus, alongside such dignitaries as Mikhail Gorbachev and Lech Walesa. The program’s most inspiring moment came at the end, as conductor Ivan Fischer invited unknown local musicians to perform alongside his orchestra in an unrehearsed performance of Beethoven’s act two finale of Figaro. As the musicians reached a crescendo — a chaos so beautifully and seismically realized on a stage, in the seats, and from the rafters, where were invited to sing — it was at that moment I felt the closest to what I might have felt as a wall crumbled on November 9, 1989.

——————

Chris Carl, WDEL, Wilmington, DE

(Berlin) — Eight-thousand balloons, placed along the path where the Berlin Wall once stood, were released into the night sky Sunday, marking the 25th anniversary of the fall of the wall. But the celebration in this once divided city has also been a time of reflection on the East German communist state and German reunification.

While the atmosphere was similar to Times Square on New Year’s Eve, the meaning of the moment was not forgotten. Videos documenting the wall and East German oppression were shown on large screens at several key points along the former wall. Audiences cheered when the videos showed the opening of the gates, but when the presentations were over, many older viewers were in tears, left to remember how life used to be.

“We have taken advantage of this opportunity,” Berlin Mayor Klaus Wowereit said during a ceremony at the city’s Konzerthaus am Gendarmenmarkt. “Thousands have taken to the streets to celebrate. This is unbelievable. Berlin is happy!”

Wowereit thanked the civil rights advocates of 25 years ago for making the fall of the wall possible. “They overcame their fears of the omnipotent because their yearning for freedom was stronger. It was a long battle and there were many victims, including people who died at the wall for trying to escape. They were driven by their desire for freedom. We should not forget them. We will not forget them,” Wowereit said.

The Wall falls overnight

The story of how the wall eventually fell on Nov. 9 is a story of serendipity. That evening, in a televised press conference, Guenter Schabowski, a senior Communist Party official, was asked when travel restrictions would be lifted. Schabowski clumsily looked at his papers and with uncertainty in his voice said “immediately.” What he failed to say was that East Germans would still be required to contact the government and have paperwork in order to allow them to freely cross into West Berlin.

At 11:30 p.m., facing a reported 20,000 East Germans who were clamoring to get out, a commander at the Bornholmer Street crossing — unable to reach his superiors for orders on what to do — ordered guards to open the gate. The wall was breached, and, in essence, the Cold War was over.

“Many (people) woke up the next day and the world was changed,” said Eberhard Diepgen, former governing mayor of Berlin. “And I would not have preferred it any other way.”

Germany’s 9-11

November 9 (connoted in Germany as 9.11 — the day followed by the month) is actually a very significant and dark day in German history.

Kaiser Wilhelm was dethroned on Nov. 9, 1918, ending the monarchy and giving rise to the German republic. On Nov. 9, 1923, 16 people and four policemen were killed in a failed attempt by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party to seize power in Munich. And on Nov. 9, 1938, in what today is known as Kristallnacht, or “The Night of Broken Glass,” Jewish synagogues were burned, leaving more than 400 Jews dead.

“It is a day of shame and a prologue to the most horrific crimes against humanity,” said Martin Schulz, a German who has been the President of the European Parliament since 2012.

It’s believed that is why the East German government chose November 9 as the day it decided to no longer patrol the wall and open its borders.“There was a readiness to be proud of this day,” former Mayor Diepgen said.“The memory (of Kristallnacht) goes hand in hand with the conviction that never again shall such tragedies happen,” current Mayor Wowereit said. “There can be no room for hatred or violence. We need to look beyond ourselves and embrace diversity and differences.”

Reunification still a work in progress

It has been almost 25 years since German reunification, but not all Germans feel unified yet. Deutschland’s victory in soccer’s World Cup this past summer in Brazil certainly helped, but government officials and civilians agree that the reunification process is not complete. “Full reunification will still be 10 to 15 years from now,” said Diepgen. “It will take another generation.”

The process may have been more complicated than anticipated more than two decades ago. Yes, the people on both sides of the wall were German, but many things had changed during their separation between the time when the wall was erected in 1961 and when it fell in 1989. “The east knew the west better than the west knew the east,” Diepgen said. He attributed that in large part to the media, as East Germans were able to see and hear — and craved — western media. “But there was also a lack of respect (for the east) by the west.” Diepgen said.

As the country was reintegrating, many East German businesses and industries were purchased by West German companies and eventually shut down and closed. “Yes, the bad parts of the GDR (German Democratic Republic) were lost,” said Raimund Grafe, chief of the Representation of the Free State of Thuringia, “but so were many of the good parts.”

Ironically, Grafe said before reunification, the people of East and West Germany were united in the belief and efforts that the GDR needed to be ousted, but some of that unity was lost after the fall. There are also former East Germans who will tell you that, despite oppression by their government and a lack of many human rights, life in the Soviet Bloc was not as bad as you might be led to believe. “We did not have the freedoms that westerners enjoy, and we had a wall that wouldn’t allow us to access the west, but everyday life wasn’t bad,” one former East Berliner was heard to say.

“Starting over was hard for many people,” said Mayor Wowereit. “Some felt they were losers. Some were exploited by profiteers. We want to remember all of those people who suffered setbacks. Those who weren’t felt welcome.”

The Wall today

The wall today for the large part is no longer standing, as illustrated by the lighted balloons. Some portions do remain, notably the East Side Gallery, the longest surviving section which has been turned into an open-air art gallery.

There is also a portion of the wall still intact at the Berlin Wall Memorial, where areas once known as “the death zone” are now filled with the laughter of families playing on a green lawn. The names and pictures of the 138 people who died while trying to cross the wall are displayed nearby. Checkpoint Charlie remains intact, but instead of armed guards checking paperwork, two men dressed as American GI’s pose for pictures with tourists, and across the street is the ultimate symbol of American “culture” — McDonald’s.

The final lesson from The Wall

During this 25th anniversary celebration, much has been made of its non-violent demise. It could have ended much differently, had border guards decided to use force to keep the gathering crowds of Nov. 9 at bay or even fire a shot into the air to restore order, or if one of the East Germans clamoring to cross the wall to freedom had wrestled a firearm away from a guard for an act of vengeance. “The fact that banners and singing were able to triumph over tanks and violence, this is what we need to bear in mind… to understand the incredible courage and the fears they had to overcome to live in freedom,” Schulz said. “November 9th shows walls can be overcome with determination and, yes, by peaceful means,” Wowereit said.

There is now famous video footage of a young East Berlin woman asking a border guard if she could cross into West Berlin to see her parents. When the guard said “yes,” she kissed him. In the end, the wall had fallen not with tanks and gunshots, but with hugs and kisses. There were tears, but they were tears of joy.

——————

Vince Duffy, Michigan Radio, Ann Arbor, MI

As a cynical political science major at Kent State University in the early 80s, I once said there were three things I didn’t believe I’d see in my lifetime: the end of apartheid, a Palestinian state, and the fall of the Berlin wall. History has shown I didn’t know what I was talking about (although I’m not holding my breath for that Palestinian state anytime soon).

This past November, Germany celebrated the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin wall. I was fortunate enough to be included in the celebrations along with handful of other U.S. journalists as the guests of the RIAS Kommission. The quick four days in Berlin were extremely informative, constantly fascinating, and at times very touching.

The wall fell in November of ’89, and I was in Berlin the following summer while large portions of the wall still stood, and German unification was far from complete. So I knew a bit about the history of the wall and the significance of its removal.

But the agenda put together by RIAS allowed us to speak to experts we would have had trouble locating without help, including longtime Germany based journalists, a man who served time in an East German prison for smuggling people out of East Germany in his car, a painter who initiated the artist group that painted the remaining wall as a gallery, and the former mayor of Berlin.

But even more fascinating were the ordinary people we were able to speak with who weren’t on the official interview list.

For example, the man working as the translator for our dinner with the former Berlin mayor had amazing stories to tell. He grew up in East Berlin and was 27 when the wall was opened. He shared stories of the difficult transitions that occurred during unification, the lost jobs and security of state care, the overly optimistic expectations of freedom and the disappointments that followed.

The emotions of average Berliners on the street were also interesting. While there was definitely a festive and celebratory air around the event, there were deep emotions just under the surface.

The city had set up a number of large screens around the Brandenburg Gate and Checkpoint Charlie that looped a roughly 20 minute documentary about the construction and fall of the wall. Throughout the weekend large crowds gathered to watch the film in silence. I stood to watch the film on Friday night, and when it was finished, I was surrounded by adults in tears, many of them making no attempt to hide their emotions.

Winding through the center of Berlin, where the wall once stood, were 8000 white balloons that were released on Sunday evening, the actual anniversary of the checkpoints being opened at the wall. The release of the balloons was not very well orchestrated, but the large crowds throughout the city cheered as the balloons in their section rose one-by-one into the air.

Some of the balloons didn’t launch correctly, and groups of people from the crowd would work together to eventually release the balloon, prompting further cheers from the crowd.

For me, the most touching moment came during a program for dignitaries at the Konzerthaus on Sunday afternoon. With former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and Polish Solidarity leader Lech Walesa in attendance, as well as German and European leaders, and even some U.S. mayors, there was a magnificent performance of the final scene of the second act of Beethoven’s “Fidelio”.

What made it so interesting was that the performers included anyone from any of the Berlin orchestras or choirs who wanted to participate. The performers included internationally known opera singers and musicians, and unknown musicians from local Berlin groups. Like the unrehearsed events of 25 years ago, there was no practice for this performance.

But as the crowded musicians on stage were joined by vocalists popping up out of the crowd around the Konzerthaus, it was a demonstration of the unity now found in Berlin as images of the wall coming down flashed on a large screen.

While this trip was much shorter than the typical RIAS program for American journalists, its focus on a single important event and the access it provided made it a great success. It’s another example of the importance of the partnership RIAS has with many American journalists.

Danke Schoen for this amazing trip and chance to learn more about this episode in history.

——————

Jonathan Ebinger, RTDNF, Washington, D.C.

——————

Ursula Reutin, KIRO Radio 97.3FM, Seattle, WA

“It’s complicated.” That’s the phrase I heard over and over again as Germany celebrated the 25thAnniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 2014. To be honest, I naively expected an overwhelmingly positive assessment of how life has changed since that monumental day when tens of thousands of Germans started tearing down the 96-mile concrete wall by hand. But Germans are not known to sugarcoat anything. After hearing the unvarnished stories of residents and politicians from both sides of the former border, I have a much deeper understanding of why the impact of that turning point in history is so complex.

When I arrived in Berlin, I immediately sensed the pride of a country preparing to host a massive event for the whole world to see. My taxi driver pointed out Potsdamer Platz and the beautiful art installation featuring thousands of illuminated white balloons, lining the path where the wall once stood. When he found out I was an American radio journalist, he shared that his life after reunification was “not perfect” but much better than it was when he lived in East Berlin, in the shadow of the wall that had ripped his family apart. He was happy that he could raise his children without the fear of constantly being watched by the secret police but this freedom has also come with costs. I wanted to hear more but our conversation was cut short when we reached the hotel. As it turns out, his sentiments were echoed by many other Germans we encountered during the RIAS Berlin program.

On our second night, we were waiting for former Berlin Mayor Eberhard Diepgen to arrive at a restaurant and struck up a conversation with his translator. Hartmut Voigt grew up in East Berlin, and spent many nights listening to hours of programs broadcast by RIAS, just over the border. His love for the Beatles inspired him to dream about life on the other side of the wall. It wasn’t until the mid-1980s that he thought a unified Germany would be remotely possible and the idea of being able to travel freely was exciting for him. But he also says their family had a good life in East Germany. His parents had jobs, they had a comfortable home and they never worried about having food on the table. When the wall came down, Voigt was in his mid-20s and he was able to make a smooth adjustment and take advantage of the new opportunities. It was much harder for his parents, who were among the millions who lost their jobs and are still struggling to find their footing. As Mayor Diepgen aptly put it, “there were many winners, but there were also losers after the fall of the wall.” While November 9, 1989 marked the end of the Cold War, it also marked the beginning of a dramatically different way of life that many were not prepared to handle.

I was surprised to learn that for many East Germans, the euphoria quickly wore off once they got their first taste of freedom and burned through their welcome gift of 100 marks. They were faced with the realization that even though Germany was no longer split, there were stark differences between the two halves. Understandably, it was hard for them not to feel like the ugly red-headed stepsister. Their buildings and roads had suffered from decades of neglect; their political system went extinct overnight and their tiny Communist-built Trabants looked out of place next to the Mercedes and BMWs in the West. During the past 25 years, Germany has spent two trillion euros to rebuild the East, which now has good roads, beautiful government buildings and new sky rises. But Raymond Grafe with the State of Thuringia says when the wall fell, younger easterners fled to the West in droves, unemployment soared and there wasn’t enough industry left. He also says there were some unscrupulous West German business speculators who made a killing by buying up plants and then shutting them down a few weeks later. Grafe says this only added to the disenchantment of East Germans who already felt that unification was more of a “takeover” by the West and they longed for their former way of life.

That sentiment is hard for some West Germans to understand. When I asked a longtime West Berlin resident what he remembers about the night the wall fell, he said he was at a bar and noticed that large groups of people “dressed in terrible clothing” suddenly filled the place to celebrate the historic moment. While he is happy the wall no longer exists, he’s still bitter that he is paying extra income taxes to help rebuild the East. But I believe many more Germans share the sentiments of my sister, Christina, who’s lived in Bielefeld since the early 80s. Even though Germans already pay some of the highest taxes in the world, she felt very emotional about reunification and felt it was not only her duty, but a sign of solidarity to pay the seven-and- a-half percent increase in income taxes.

Through the speakers we met in the RIAS Program, another theme emerged: the Germans’ relationship with the U.S. is also very complicated. Germans are extremely thankful for the United States’ role in helping them rebuild West Germany after the devastation of World War Two. During the ensuing Cold War, Germans and Americans were staunch allies. Now, twenty five years after the fall of the Wall, Germany is the world’s fourth largest economy and the driving force in the European Union. As such, Germans, under the leadership of Chancellor Angela Merkel, are not satisfied with just being a junior partner in the alliance. I believe this dynamic also adds to the complexity of the post-unification story, especially given recent developments in Ukraine and former Soviet Union President Mikhail Gorbachev’s assessment that we’re “on the brink of a new Cold War.” Germany is one of our strongest allies and I feel that all Americans need to understand its global importance, beyond when the Germans win soccer’s World Cup.

As the daughter of a German father, I have visited the country many times but this RIAS Berlin trip was truly eye-opening. My father was in Berlin on German Unity Day on October 3rd, 1990, when the reunification was formally completed. As a young editor, I put him on our radio station, live, as the country celebrated that momentous occasion. When I was chosen to be part of the RIAS program, we were both thrilled that I would witness the events surrounding the 25th anniversary and learn more about a country that has a special place in our hearts. Through this wonderful opportunity, I got a very realistic picture of how Germany has changed for the better but also learned of the problems that still exist. Although there isn’t much left of the actual wall, there are still political, economic and social differences that divide the country.

Yes, it is complicated, but I now realize that the fall of the Berlin Wall is an awe-inspiring story that, after 25 years, is still very much in the making. As Mayor Diepgen told us, “perhaps it will take one or two more generations before the remaining barriers come down.” I look forward to future trips to Germany to continue seeing this beautifully complex transformation.

——————

Julie Rosene, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI

Vantage Point Berlin

The year was 1971 and a sixteen year-old girl from Milwaukee, Wisconsin was traveling on a six week European trip with her high school class. Paris, London and Rome were at the top of her list for cities to explore. What she did not expect was the profound feelings she would experience during her visit to Berlin!

At that time, the city was divided by a threatening concrete wall separating the Democratic city of West Berlin from Communist East Berlin. On this particular day, this young midwestern high school sophomore hopped on her tour bus and proceeded to make her way through Checkpoint Charlie to get a first-hand view of “the other side.” East German border guards wielding menacing rifles took their time meticulously scrutinizing each student’s passport before entry. The bus of high school students was totally silent, a rare occurrence for a group of boisterous teenagers traveling abroad. But on this occasion, obedience was absolutely required.

That girl was me, forty-three years ago, and I still vividly remember the intensity of the East German border guards and driving through a very austere East Berlin. I can still recall the guard towers, barbed wire and remnants of buildings left standing after the war; a colorless city, void of pedestrian activity, and seeing up close the oppressive lack of freedom East Germans faced behind the wall.

Fast forward to 2014, and I found myself back in Berlin, this time as the Director of Special Projects and Digital Media instructor from the Diederich College of Communication at Marquette University. I was traveling with a group of accomplished American journalists on a German/American exchange program as a guest of the RIAS Kommission, brought together to share in the celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall.

I found Berlin in 2014 a much different place. The city, now unified, was dynamic and vibrant, full of young artists, musicians, families and tourists. Restaurants, shopping malls, museums, concert houses and modern architecture were juxtaposed with the historic landmarks of the past. Berlin was now a cosmopolitan city, and it was difficult to discern what was west and what was east! A once militarized and divided city was now bustling with the combined energy from all of its citizens.

The agenda for our four day visit gave us the unique opportunity to speak with government officials and experts on the transition to reunification; a meeting with a man who served time in an East German prison for smuggling people out of East Germany; and a conversation with an artist responsible for using his ingenuity to encourage artists from around the world to use a seventy foot section of the remaining wall as a blank canvas for freedom of expression.

The RIAS Kommission gave us this “all access” pass to uncover the multilayered and complicated story that lay just under the surface. A chance conversation with an interpreter revealed his personal story as a young man growing up in East Berlin. He shared his perspective on the government’s enforced limitations for travel, restraints on freedom of thought, families kept apart and under threat of death and the fear that a Stasi Interrogator was watching your every move.

Celebrating the anniversary of the Fall of the Wall was indeed a huge joyous party for Germany and the world! November 9th is a date that is traditionally a somber day set aside to memorialize the anniversary of Kristallnacht. But for once, this year, Germany allowed herself to rejoice and celebrate a positive event that brought freedom to the oppressed citizens on the other side of the wall and helped bring an end to the Cold War.

And what a celebration it was! Eight thousand illuminated white helium balloons bearing messages of hope and marking the stretch of the wall were released into the air as a visual expression of freedom. Music ranging from Peter Gabriel performing at the Brandenburg Gate to the symphonic flash mob of Beethoven’s Fidelio at the Konzerthaus were just part of the festivities.

And so, on this November 9, 2014, more than a million people, including me, forty-three years later, came together to remember the revolution that resulted in a remarkable peaceful reunification in l989.

My visit in 2014 helped me to reflect back on my first impressions of this once divided city. Still vividly recalling how I stood confined on that tour bus in 1971, fearfully intimidated by the East German boarder guards towering over me. For me, this feeling lasted just a day, but for some East German citizens their days of confinement turned into a lifetime of oppression.

Stepping outside of my comfort zone as a sixteen year-old girl to witness human suffering and then returning years later to join in the celebration of this breakthrough to freedom, afforded me a front row view of history and a unique perspective of this momentous event.

The Fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of the two Berlins serves as a remarkable example of the strength of the human spirit and the power of people to impact profound and long-lasting change. It is a lesson I hope will inspire my students to realize that their “voice” has impact and that each of them has the ability to step outside their comfort zone to make a difference in the world.

——————

Ric Schroeder, KNX CBS Radio, Los Angeles, CA

On November 9, 1989, I was “ripping and reading” dispatches from Berlin coming into the KFWB newsroom in Los Angeles via Associated Press and United Press International teletype machines. All of us watched the television monitors in the newsroom in amazement at what was unfolding and hoping that it would not go the way of Tiananmen Square just six months earlier. I was working with a group of veteran journalists who were unanimous in the belief that this day would never happen in their lifetimes. But now it appeared that “The Genie was out of the bottle!”

Throughout the Cold War, Americans had been warned of the “Domino Theory,” that as one country fell to communism, others would fall like a line of dominoes. This night, we were seeing the “Domino Theory” in reverse.

So many things you can’t predict, such as my future wife being among the thousands of Berliners as she rushed from her home on Knesebeckstrasse to join in the celebration along the Kufürstendamm that evening.

It would be the year 2000 before I would have the opportunity to visit Berlin. There was construction everywhere, with some proudly boasting that every construction crane in Europe had been brought to Berlin. But, I came away with the impression that great debate continued over what would stay and what would go. Remnants of the Wall remained, but to the dismay of others, the Palast der Republik was scheduled for the wrecking ball. I could sense there were still many in the East and West who longed for the “good old days.”

I returned to Berlin in 2003 and 2005 (with my German born wife, Petra) and each time I was impressed with the steady progress. The transformation of Potsdamer Platz from “no mans land” into a world-class shopping and entertainment area. The gentrification of Prenzlauerberg was underway. Young entrepreneurs from across Europe were flocking to Berlin. The city had taken on a more cosmopolitan feel.

In 2006, Germany hosted the World Cup and many told me how it was the first time they truly felt united as Germans. Being proud of their country and displaying the colors was exciting for them.

In 2009, I was fortunate to attend the 20th anniversary of the Fall of the Wall. I remember meeting with young journalists from Moscow, Warsaw and other cities throughout Europe. For them, it was a history lesson taught in school, or stories heard from their parents. There were many among the young eastern European journalists subscribing to “revisionist” versions of history.

Which brings me to 2014, and the wonderful opportunity through RIAS Berlin Komission to take part in a highly informational five-day program leading up to MauerFall 25. From the welcome luncheon with RIAS Chairman Thomas Miller to the amazing 360 Panorama “The Wall” and Kani Alavi’s enthusiastic presentation at the “East Side Gallery.” Breakfast meetings with journalists Erik Kirschbaum and Thomas Habicht, with Erik providing the perspective of an American journalist working in Berlin and Thomas offering his interesting and often amusing insight into German re-unification and relations between Berlin and Washington. I especially enjoyed our dinner conversations with Karsten Voigt and Eberhard Diepgen. A chance for me hear political leaders, journalists and others describing life in Berlin; then and now. I appreciated the open and honest discussions. The acknowledgements that mistakes were made along the road to re-unification and relations between Berlin, other members of the European Union and Washington were sometimes strained. However, the divisions were overcome and a quarter of a century later, Germany is a united economic power.

I enjoyed seeing the thousands of young people who took part in the 25th anniversary celebration and was touched at seeing my wife describe with tears in her eyes as she stood among the crowd on November 9, 2014 and flashed back to a moment 25 years ago when she watched East Berliners celebrate their new found freedom in the streets of West Berlin.

——————

Greg Sutton, Manhattan Neighborhood Network, New York, NY